I enjoyed reading Code 2.0, mostly because (and I never thought I’d ever hear myself saying this) it was refreshing to hear the consitutional lawyer’s opinions and perspective over a bunch of over-stimulated technologists/academics. Yes, friends, Hell has just frozen over.

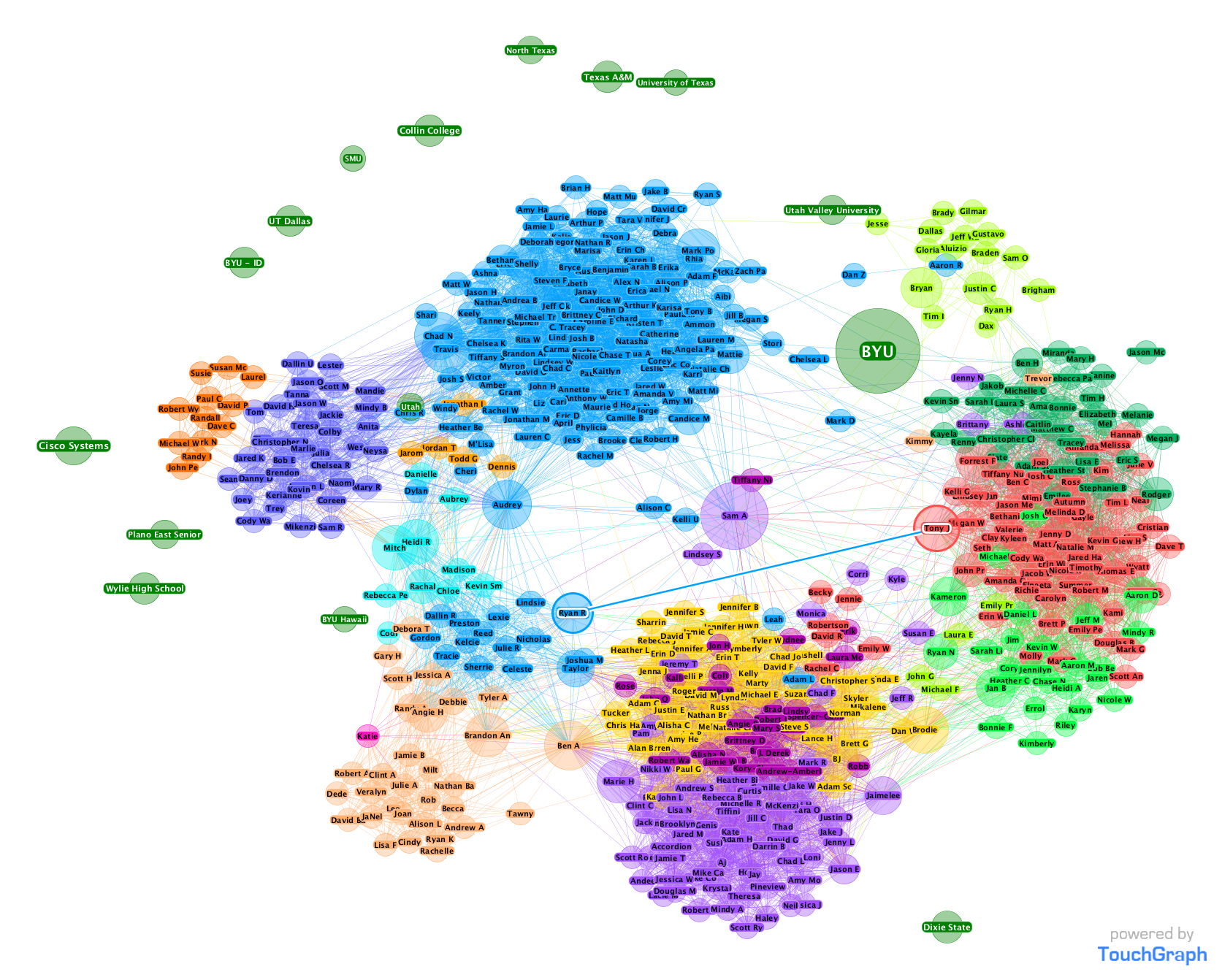

What I really enjoyed the most was his allegation that in our new reality – specifically in cyberspace – we can simply ‘recode’ the situation if we don’t like the laws of the universe we’re operating in. Especially since Web 2.0 is a highly interdependent and contributory medium (one in which everybody not only brings their own content but also can bring their own programmatic coding which may or may not rely on multiple websites and APIs for functionality), you can literally reprogram the virtual space you are in to obey the laws you want.

I felt like, in the section on translation, he was indicting constitutional “originalists” quite fiercely.

This kind of translation speaks as if it was just carrying over something that has already been said. It hides the creativity in its act; it feigns a certain polite or respectful deference. This way of reading the Constitution insists that the important political decision have already been made and all that is required is a kind of technical adjustment.

Constitutional Originalism, popularized in recent years by Justice Scalia and now coopted (at least in part) by conservative political factions, presupposes that one can actually guess what the founder’s original intent was; and lawyers (above all others) should understand the difficulty in proving intent even for the living (no less, the intent people who lived over 200 years ago).

Perhaps I’m revealing my own biases here, but I do believe that laws have to be made given the present reality, and I believe that Lessig makes a nice case as to the perils of too-simply translating old beliefs into the new, virtual world. As Lessig points out, in the late 18th century, while the founders saw the need to protect citizens from government trespass into their personal property space, they put no such limit on the public space. And now, the debate continues to rage over whether the Internet is an inherently public or private space, who owns the data that is put thereon, and what means of legal recourse governments and individuals can expect in this new reality.

In the chapter on copyrights, Lessig opines that the pendulum is certainly swinging in favor of copyright holders and the public space perception; that cyberspace is a place to be policed. I do believe it is, but it is also a place that needs to be policed through the front door. We need statesmen who will courageously define the virtues and vices of governance in this space, rather than politicians who are bought and sold by corporations and copyright interests – whose primary motivation is control.

As Lessig points out, though, we have seen a change of the “code” since the DMCA was put into place. The implementation of the law, in some ways, backfired on the corporations and government that ended up implementing it. We now see that most music providers who used the draconian DRM measures have now backed off and simply watermark purchased files with the licensee’s information. They have responded to consumer demand for open formats over the control that was promised and delivered through DRM. I count this up as a win for consumers.

Video is next in this space. What mp3s were in the late 90’s, videos are today. Netflix is certainly the first to effectively and massively commoditize this space (sorry Apple), but they are hawking a subscription model rather than a content ownership model. While this can be a good deal for consumers, it leaves ultimate control in the hands of the corporation, who simply can’t be trusted to make all the right choices that all the consumers will agree with in the long run. Since consumers aren’t owning the content one has to wonder – how long can they hold a market lead? Until the network speeds up a bit more (it’s underway) will this finish playing out.