What most interested me in this week’s readings was Ong’s firm assertion that “oral literature” was a term that should be abolished from our lexicon, and that there really can be no such thing as “oral literature”.

His assertion that written language is really just a technological instrument to capture oral expression got me thinking more about the technological instruments we use today. He points out that, when the printing press was invented, people thought that having books would make people more stupid, just as people fear today that calculators, smartphones, and social networks are making people more stupid and less engaged. Yet, books have become so ingrained into our society (and rightly embraced for centuries by academia, the thought-leaders of society) that no one questions their usefulness, mortality, or place in our society.

In fact, as a father-to-be, it’s pretty odd to think that it is encouraged (or demanded, depending on who you talk to) that I start reading to my child long before he can even speak. If you put it in Ong’s terms, I am supposed to introduce this child to the technology of literacy before the child has any capacity to absorb or be affected by it. I would imagine that ‘expert’ opinions would be more mixed if I advertised that I was going to spend an hour a day with my child on the computer, reading to him from programming websites or watching video tutorials on Objective-C programming – or even just watching mindless YouTube videos. Many would say that would be, at worst, rotting his brain and ruining his eyesight or, at best, wasting his time, while I would assert that I was tuning his senses for the world in which he will live and inundating him in the technologies he will need to understand to thrive. There is no question among the ‘experts’ or the general populous that reading to my child from a very young age will be a fruitful, worthwhile endeavor that will forever enhance his chances of intellectual and financial success in this world. How many centuries will have to pass before it will be just as acceptable to introduce children to other technologies that extend orality, just as books and printing have done? Many parents purposefully shield their children from technology, especially as the child turns into a teenager who might not only be inadvertently exposed to inappropriate material, but who might also seek it out. The immersive, two-way experience is feared now even more than the one-way, highly filtered experience of television was as I was growing up in the 80’s and 90’s. (I recently watched 90’s rapper Snow’s music video for the hit “Informer”, and was actually kind of glad that MTV (the version that played music videos) was banned in my house… yikes!)

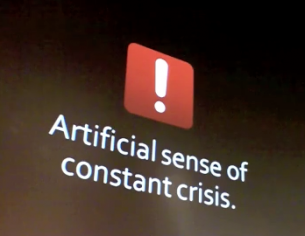

Also, there is a great concern out there among the older generation that, by being extra-fluent in the newer technologies of communication, we are somehow losing our ability to communicate in the traditional ways. They fear that their preferred modality of reading, writing, and conversation (all in long-hand, if you will) are suffering at the hand of abbreviation encouraged by txt-speak and tweeting.

Could it be, though, that we, as a society, are just becoming more efficient at communicating? Ong does point out that though the fundamental building blocks of our language have remained relatively unchanged, there was an interesting time in the evolution of language when vowels were not a part of written language. Perhaps a parallel can be drawn between that and today’s current love affar with abbreviation and acronym-ization. (i.e. “u” for “you” and “AFAIK” for “as far as I know”)

In fact, changes to the ‘technology’ of communication are much more prevalent now than ever, and yet resistance to that change is still alive and well. Every time Facebook makes any modification to their profile design, there is a group formed immediately to vehemently oppose it and statuses and comments abound on how everyone hates the change. Though that is certainly not as fundamental a change as attempting to redraw an entire alphabet (as the Koreans were wont to do, as Ong points out), if we view written language as a technological construct that captures the oral communication, then the Facebook resistance is a natural extension of that technological change.

One last parallel I will draw out that was inspired by Ong’s writings is about his section on “learned” languages, in which he draws the history of the rise of “learned Latin” after it had given birth to its child languages. Latin became a language that was learned from the written, then spoken only if necessary (as opposed to being learned from the spoken). This made me consider, as a white male coming into my 30’s, my increased usage of urbandictionary.com. At least once every few months, I find myself turning to the urban dictionary to understand a word or phrase that I simply can’t get from the contextual clues. In a way, that website’s existence is also a betrayal of orality. These words and phrases are coined without spelling, but have to be captured, recorded and made available to pencil necks like me. It’s a great resource for me not to look stupid, but a betrayal of the way the language is supposed to be learned and used.